Joan Gaspar Studio

Interior design project by Twobo

We interviewed TWOBO, the architecture studio that designed Joan Gaspar’s new atelier.

We knew it would be interesting but didn’t realise just how much.

A Renaissance painting, a supply of recycled wood from the old Marset showroom in Barcelona and a well are some of the key elements in this story, which has been a pleasure to discover, revealed by the people behind it.

To start with, tell us a bit about the process and the relationship with Joan Gaspar.

Is it more difficult to work for a designer than another type of client?

No, quite the opposite, it’s easier. There’s a shared language and, above all, some concepts no longer need to be explained: scale, composition, texture… Of course, at the same time it’s also more demanding.

With Joan there’s a relationship of trust. The trust he placed in us when editing our grandfather Manuel Valls Vergés‘ MVV lamp—our grandfather was Coderch’s partner in his architecture studio—and the trust we place in him and his decisions. From those conversations and visits, affinities emerged that, over time, have become two projects.

There’s also another curious point: Joan loves architecture; he understands it and jokes about the idea of coming to our office someday as an „intern“. And it’s a similar situation with us with design: we like it and we approach it more tangentially, through furniture and lamps.

What does Joan like most about you and what do you like most about him?

We like Joan’s confidence and the enthusiasm he puts into things. He never goes halfway with his projects and that helps keep things clear. When we work together he calls us every day; it’s like having him with us. This involvement means the project is carried out by 8 hands (6 at Twobo plus his). It’s a constant conversation, and with unexpected plot twists, like what happened when we recycled some wood from the showroom Marset had in Barcelona for this studio.

What’s the way you like to work? Do you have a methodology or do you approach each project differently?

More than a methodology, there’s an insistence.

On one hand, we want to thoroughly understand the place we’re working on: its history, the materiality. So that our arrival doesn’t bring about an abrupt end but respects what already exists. There’s always something more important than oneself. It’s, perhaps, a form of respect.

But respect can’t act as a brake either, as is the case with excessive politeness. You have to add the intuitive part, that aspect that’s more about hand movements and gestures, which we develop in the office with lots of sketches and models. That’s where the less obvious things appear, the things that are often hidden or not visible.

What was the place like before your involvement? What was it used for?

The space was practically the same; the beauty of this place is that the magic was already there, we just had to make sure we didn’t ruin it. When we arrived, a renovation had been started but it wasn’t finished. The whole thing was very raw, with the original stone and brick exposed and rough concrete floors with the supply pipes poking through. Joan told us it had previously formed part of a water cistern in upper Barcelona, and we think that one of the spaces, the office, was the well that supplied the cistern.

What challenges did the project pose and how did you manage to overcome them?

It was a semi-basement with a very irregular floor plan, almost labyrinthine, as if the spaces had been joined at random. Joan didn’t mind that too much. Sometimes absolute clarity erases doubts but it’s good to doubt, in our profession and in his. That’s where interesting detours appear. There’s very little to discover in a straight line.

The layout reflects that idea of losing oneself. You just have to see how Joan moves from his office to the model workshop.

The project is renowned for its use of a wide range of materials and the contrast between regular and irregular forms.

Why did you arrive at these solutions?

The irregular was already there and it was good. Being underground, some of the walls have humidity. We told Joan that, to eliminate it, we’d have to cover them but we decided it was better to leave them as they were, untouched. So the new doesn’t touch the old walls; they’re allowed to breathe.

We took advantage of some of the wood that Joan had got from the old Marset showroom in Barcelona they were dismantling to renovate. The wood was perfectly straight and it didn’t make sense to adapt it to the different shapes of the space, so we built rectangular wooden „carpets“ that fit into the spaces but without touching them, leaving that air we mentioned, for the walls to breathe. Those gaps also provide space for the wiring and other installations and protect the wood from humidity. To provide access to the installations we covered the gaps with dark gravel, further emphasising the separation between the “carpets”.

The idea of crossing, of going from one place to another, is important. Each space begins and ends in a different place and that’s reminiscent of certain gestures in Japanese culture, which is always worth paying a small tribute to.

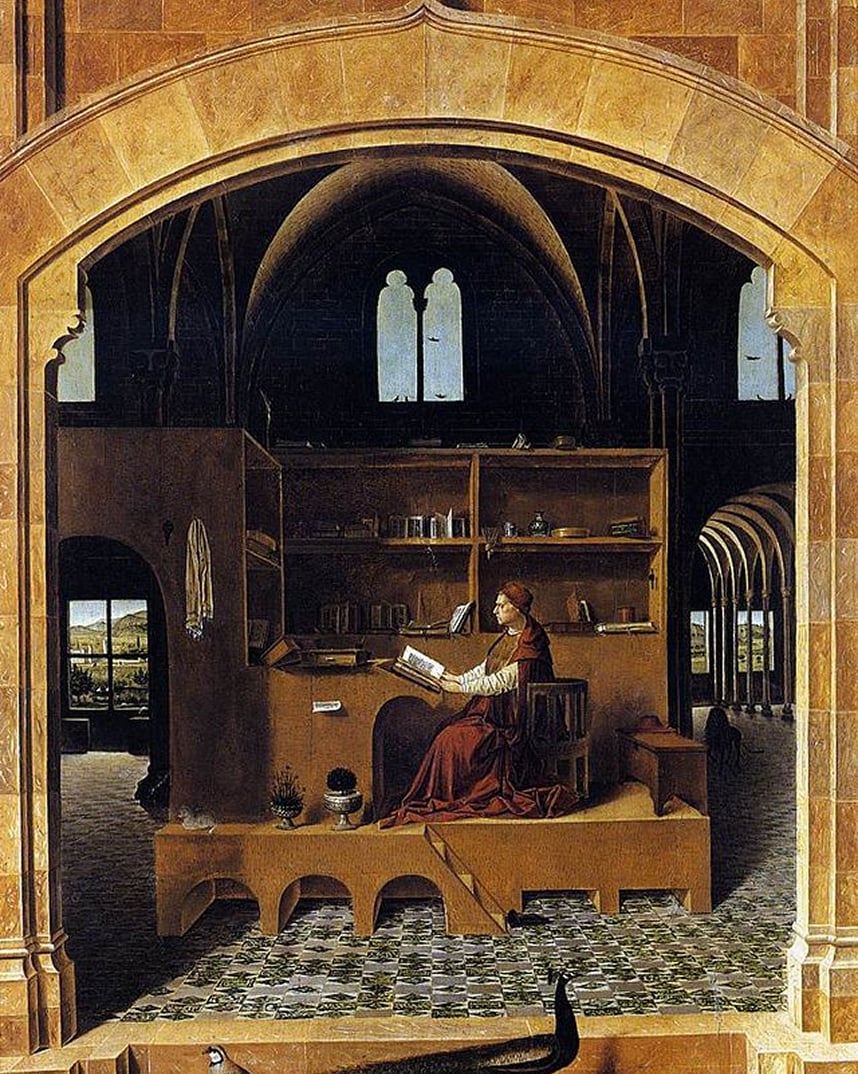

A painting served as inspiration for the project.

Can you tell us a bit about this story?

It’s quite a famous painting by Antonello da Messina, an Italian Renaissance painter.

The image depicts Saint Jerome in his study, which is situated within a large cathedral.

It’s a painting that noticeably plays with different scales. The study is made of wood and is placed like a large piece of furniture within the Gothic architecture of the church; like one home within another. This large piece of furniture has shelves, desks and drawers to store the Saint’s manuscripts and objects. Saint Jerome is always pictured dressed in red and surrounded by animals, specifically a lion.

Joan has a beagle called Lupa and we’ve never seen him dressed in red, but we could say that the rest of the ambience is “similar“: a character at his wooden desk, concentrated, with a host of objects around him, all within reach. A small wooden world within a larger stone one.

One is touched and used – the wood – whilst the other leaves space for something that’s harder to contain, namely thoughts; that’s why high ceilings help.

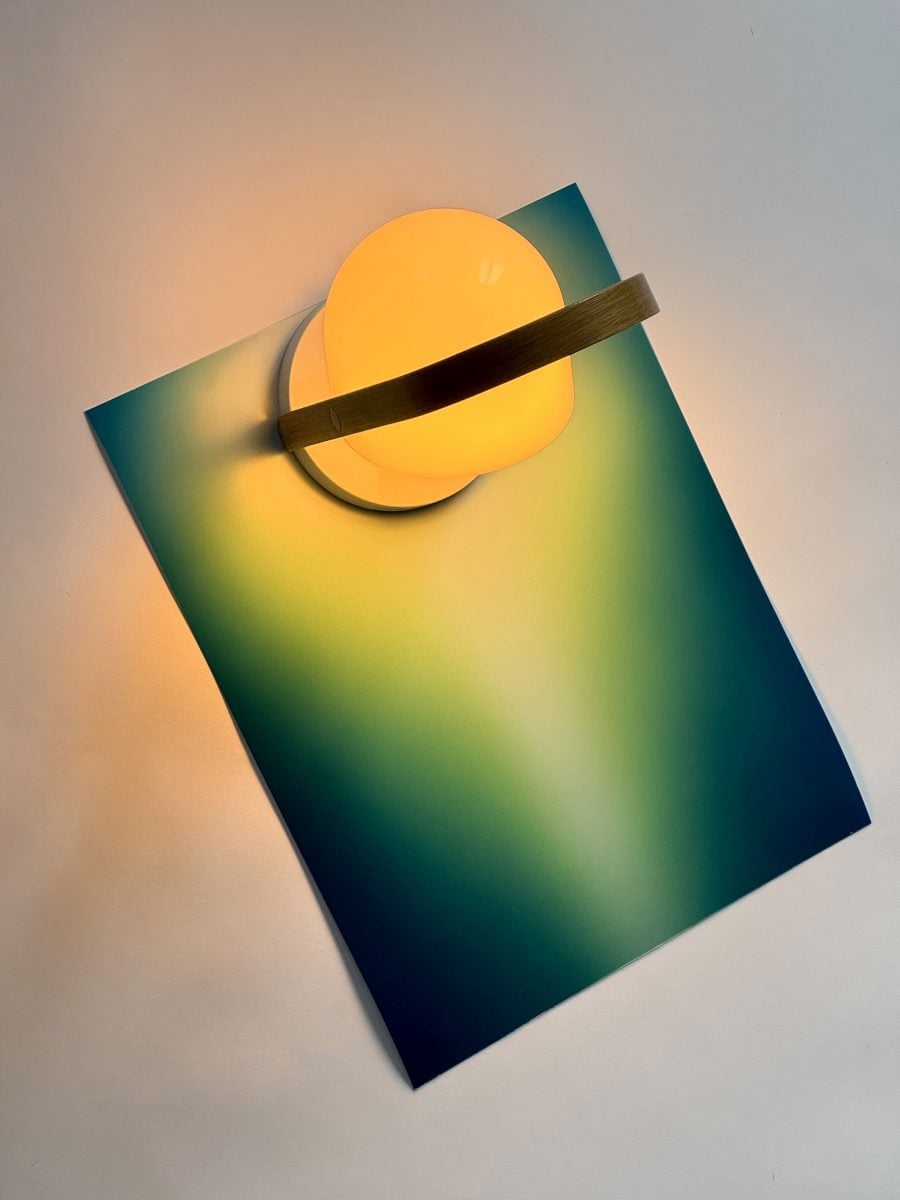

How would you define the light in this space?

It’s a gradient, a transition from light to dark; like in a cave. There’s only one illuminated façade. The work spaces are placed facing that façade whilst the prototype workshop, the office, the storage face inwards. There’s a constant polarity between internal and external.

Joan has left the outside and the terraces as two small oases.

As for artificial light, the key was versatility, so that Joan could change it easily and the whole space would be like a trial workshop. That’s why the installations are visible, easily accessible and modifiable.

In the debate between technical light and decorative light, where would you position yourselves?

For us, especially in housing projects, lighting is like another inhabitant of the house and, as such, it has its own personality and occupies a space. Sometimes you need a discreet character, sometimes one that’s striking or friendly.

Of all Joan’s lamp designs, which is your favourite?

Well, there’s three of us and we don’t agree.

Alberto: The Bohemia, without doubt, and as a standing lamp, the Jaima

María: The Polo. We had it at home without realising it was Joan’s. We bought it at Vinçon.

Pablo: The Ginger pendant and the Plaff-on

How do you think this new space will impact Joan’s work? In what aspects will he find inspiration?

I hope that, jumping from one “carpet” to another, entering the office which is like a small miniature chapel, kicking some gravel back into its place or noticing the dust released by the original walls… Architecture doesn’t always have to be easy and perfectly clean. Paul Valéry said, speaking of Degas‘ studio, that it was a place where light and dust were happy.

There’s not much difference between a designer’s studio and a painter’s.